Nantucket's Changing Tides: Preserving a Family’s Fishing Legacy, Past & Future

If judged solely on his radiant grin, sharp humor, and near-constant chuckle, you wouldn’t guess that Carl Sjolund was nearly his age. Clearly, a lifetime spent on the water and within the fishing community for seven decades has had a life-giving effect. Now approaching eighty, Carl is no closer to retirement than to giving up his life-long career harvesting Nantucket bay scallops.

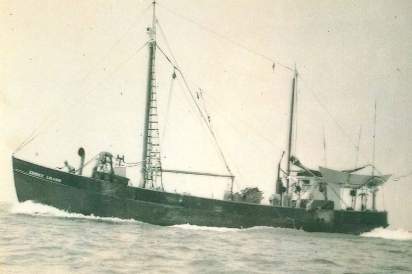

Carl is the second generation of Sjolunds to make their living off the waters of Nantucket, following in his father, Rolf Sjolund’s, footsteps. After seven years at sea on a Norwegian freighter, Carl’s father was just twenty-one when he stepped off the boat onto American soil. With barely any spoken English and only the name of a second cousin residing in the U.S., Rolf washed ashore on Nantucket in 1928. He began working as a deckhand for his cousin Dagney’s husband, a highly-regarded fishing captain named Olef Anderson. Under Olef’s tutelage, Rolf went on to build two eastern rig side trawlers of his own and raise four children on the island, sparking his oldest son’s passion for the ocean and a fishing legacy that now spans nearly a century.

Nantucket’s fishing narrative is often dominated by tales of prosperity brought by the whaling industry, yet nearly two centuries have passed since the era of hunting white whales and the present day. It’s refreshing to imagine a time when Nantucket’s docks were bustling with the vibrant pursuits of local fishermen, long after the grandeur of tall ships and prized whale oil had faded into history.

A self-described wharf rat, Carl spent his childhood down on the docks that teemed with activity along what would now be recognized as Nantucket’s downtown waterfront. Fishing schooners manned exclusively by Nantucket crews would, somewhat miraculously, make the nearly 120-mile round trip to George’s Bank, and return with fish holds brimming with thousands of pounds of groundfish carefully layered and packed in ice below deck. “I still don’t know how these guys did it”, Carl reflects. “No electronics… thick of fog, you know? I don’t know how they did it.”

Lack of regulations during the time allowed year-round, excessive fishing, leading to the virtual collapse of most groundfish stocks. It wasn’t until 1970 that an international commission could settle on fishing restrictions. Today, strict catch quotas on groundfish make it nearly impossible to make a living on these fisheries alone. This is a burden that for many fishermen has been too much to bear.

Anchored boats would “take out” their catch, delivering them to one of the fish-packing warehouses at the present location of Steamboat Wharf. Carl remembers the large wooden crates layered with fresh cod, haddock, and flounder were packed so tightly with ice, their lids bowed under the pressure as they were prepared for the long journey to renowned markets such as New York’s Fulton Fish Market and the Boston Fish Pier.

“In the fifties, the average Nantucket carpenter or plumber was probably making a dollar an hour. But the fisherman, people would say, ‘gee, you’re making more,’ but they didn’t figure they were working twice as hard. There’s no wages on a fishing boat. It’s a percentage of the catch, and that’s still how it is today.”

Carl was eager to help as a young boy, hauling gear to and from his father’s shanty on Old South Wharf and fishing with his father in the summer when school was out. The second largest ice plant on the East Coast – which serviced the public with ice for home ice boxes and the fishing community – was just a stone’s throw from the dock. One ton of ice cost just four dollars. He fondly recalls, “Boats leaving from New Bedford, if the weather was bad, they would come into Nantucket. There wouldn’t be a day where you didn’t see a few fishing boats. It was always so nice to see. Some would come in for repairs, some would come in to wait out a little breeze.” Today, these same docks service affluent visitors who flock to the Island in the summer months. They’re now the location of the fuel dock and some of the most expensive overwater rentals money can buy.

Rolf’s second fishing boat, an eastern rig side trawler, was named for his oldest son, the Carl Henry. During the school year, Carl spent many hours after school shucking Nantucket bay scallops in George Andrews’ shanty on Old North Wharf for a modest eleven cents a pound. Carl remembers water would splash up through the floorboards and only a small kerosene heater provided warmth. “It was spooky in there” Carl shivers when recalling the memory. The shanty still stands but the structure was only just recently refurbished, sandwiched between the famous row of cottages on Easy Street. Today, the iconic scene is one of the most photographed on Nantucket.

What came next was only natural: Carl commenced a lifelong career on the water after taking a chance and acquiring his scallop license at just 12 years old.

“Charlie Sayles and I became friends when we were eleven or twelve. We shared the same interests. We used to open scallops together after school. In those days, anyone could go down to the town building and get a license. One of us had an outboard, and the other had a boat, and we wanted to try it ourselves.”

Their request for a scallop permit was promptly denied when the clerk felt that they were too young but brought the matter in front of the Board of Selectmen for consideration. Carl remembers, “The lady said, ‘These two young fellas came in wanting to buy a license, one is twelve, and one is thirteen.’ The selectmen go, ‘Well, if they’re that ambitious you sell them one.’” The pair borrowed four dredges and fished their first season in a fourteen-foot skiff equipped with a 15-horsepower Johnson, and hand-hauled every tow.

Nantucket in the early 50s had little in the way of industry – a time that many current residents now remember fondly and wish they’d return to as today’s population, commercialization, and real estate swells. The island’s 3500 year-round inhabitants mainly worked for each other in local shops, restaurants, and businesses. Jobs in the town were coveted for their predictable schedule and reliable paychecks. For those without a good job, Carl recalls, “If you didn’t have something really good to do, you almost had to go scalloping.”

Although there have always been boom years and bust years, Carl is certain that the Nantucket bay scallop industry saw its peak from 1965 to 1985. Fishing was allowed six days a week and limits changed year to year, but there was money to be made for those willing to work in freezing temperatures, bone-chilling wind, and unreliable pricing. “Cheapest I ever sold was fifty-five cents a pound, but when prices reached a dollar a pound, you could get fifty pounds a day… well, that’s fifty dollars if you opened them all yourself. And six days a week, that’s pretty good.” During that time, Carl remembers the waters off Tuckernuck could sustain a hundred boats, and island businesses felt the positive effects of the scallop harvest. When thinking of the success of his scalloping career as aided by the humble scallop boat he has fished with for over five decades, Carl smiles, “She’s paid for everything.”

By the early sixties, Nantucket witnessed the half dozen draggers that would offload on the island slowly begin to disappear from the boat basin, favoring New Bedford’s port to offload and gear up for fishing trips. “You could get ice, fuel, and crew. You could get your boat repaired,” Carl states. “Some folks blame development for the decline of our working waterfront but the truth is that those fishing wharves in downtown Nantucket were built in the whaling days and were in disrepair. There just wasn’t enough money coming in to repair them.” While the downtown docks were being converted to boat slips and shanties remodeled into shops and cottages, reliable work became more abundant in building and tourism. As Rolf Sjolund’s generation of fishermen began to retire, the next generation was not there to take the helm. When entertaining the idea of a viable fishing industry returning to Nantucket, Carl had this to say. “It will never be in Nantucket. Maybe a day boat or a little dragger. Nothing big. It’s impossible. We’re not geared up for it. And if you had all those things today, it still wouldn’t help. What would be the attraction? You couldn’t unload your fish here, because it needs to be shipped off. We are Cape dependent for fuel and ice.” This fact is no more glaring when comparing the price of diesel fuel on and off the island. A recent fuel run to Stage Harbor in Chatham for the fishing vessel owned by Carl’s son, Jim, resulted in a savings of $900 compared to what he would have spent if he had purchased the same amount of fuel on Nantucket.

During the decades that have followed, fewer and fewer locals take part in the seasonal scallop fishery, yet this isn’t all due to a lack of fortitude. Scallop harvest numbers have fallen drastically in recent years. Dwindling eelgrass, runoff, and fertilizers from overfed and intensely landscaped lawns have all contributed to the decline of Nantucket Harbor’s ecosystems. Carl puts it bluntly, “The decline is the product of overgrowth. Some things you can’t control. You can’t control acid rain, you can’t control temperature. What you can control is the environment like fertilizer and runoff. You figure every time it rains downtown, all the water draining from the town goes into the storm drains. All the storm drains drain into the harbor.”

Due to the many barriers of entry facing the next generation of Nantucket’s youth, they aren’t exactly jumping at the chance to scallop or fish commercially. Unless of course, your last name is Sjolund. Jim Sjolund, Carl’s only son and the third generation to make their livelihood on the water, is now carrying on the tradition. Jim, now in his thirties, has been scalloping with his father since he was eight years old, just as Rolf and Carl did decades before. When the dredges are hauled up for the off-season, Jim fishes the waters of the Bering Sea in Alaska, helming a 125-foot-long line cod fishing vessel and crew of twenty-five. Next summer he plans to fish for lobsters east of Nantucket off of his thirty-five-foot Downeast boat named for his mother and grandmother, the Julie Alice.

Despite the issues Nantucket’s fishing industries face, Carl sees silver linings in today’s many methods of telling Nantucket’s complex and unique fishing story. He’s seen social media directly benefit the scallop fishery when it comes to seed strandings; when scallop “seed” (baby scallops) get washed ashore during storms, their fate is unavoidable without help. “With social media, you’ve got a hundred people showing up and they have never caught a scallop in their life but they want to help because they know you are trying to preserve something. Nantucket is the last commercial bay scallop fishery on the whole east coast.”

Fortunately, public interest in small-scale farmers and fishermen is on the rise, just in time for Nantucket’s next generation of young hopeful fishermen, oyster farmers, and scallopers. Island non-profit organizations are helping to raise awareness and tell the story of how the environment and the fisheries are directly linked, voicing a clear message of the need for increased care of Nantucket harbor and surrounding waters. “Land and Water Council is studying the health of the harbor and planting eelgrass,” Carl points out. “The Shellfish Association puts on the Scallopers Ball, a fundraiser to benefit the island’s shellfish management goals. People love it. Folks will come down for the weekend to push rake and maybe will get a few bushels, but how much money was spent in our island’s economy to do it? There’s a lot of benefits to it. Nantucket is the only place in the country where you can push scoop for scallops. It’s something you can do only here. I’m pretty encouraged to see young people getting out there.”

Despite the times, Carl is confident in Jim’s decision to make a living on the waters off Nantucket. “It’s no different than a young guy growing up on a farm. Is he going to go to Wall Street or does he want to stay home and milk the cows and grow corn? He’s a free spirit and fishing makes him happy. Jimmy’s the last of the hunters.” Although Carl does advise, “The lobster boat… that’s fine. But he’s got to think of other things to do with the boat. Maybe squid-fishing, maybe commercial assistance through the Coast Guard. You’ve got to have diversification. You just can’t make it on one fishery today, and the expenses go on if the boat is in the yard or on the dock. It’s all part of the game.”

Leah Mojer, classically trained in culinary arts, is dedicated to promoting biodiversity in the food and wine industries through education, food production, and retail sectors. She’s recognized for her expertise in Charcuterie, featured in Edward Behr’s “The Art of Eating,” and has published food and wine articles in island newsletters from Yesterday’s Island and Bartlett’s Farm. Leah was a founding member of 100 Mile Makers, an active member of the Nantucket Lights Steering Committee, and serves on the Nantucket Land and Water Council Associates. She also founded the Nantucket Litter Derby, which has removed 32 tons of litter from Nantucket’s environment since 2019. Leah resides on Nantucket.